Gravitas, Dignitas, Pietas

This essay was originally published as “A Vocabulary for Worship” in the January/February 2019 issue of Touchstone .

If any people in history knew it, the Romans knew how to be serious over serious things. Next to the cultured poets and philosophers of Athens, the Romans saw themselves as a race of soldiers and farmers. The religious rites that Numa instituted early in Rome’s history cultivated a deep reverence for ancestry and custom, for bonds between neighbors, and for those boundaries that designate and hallow sacred ground. Roman law reflected a concern for those spaces that must not be violated, whether they be in a temple, a city, a house, or a man’s soul. This gravity, admittedly, came along with an almost unbelievable degree of cruelty, and when the Romans did violate that which they knew to be sacred, they were capable of a kind of blasphemy which Anton LaVey only childishly imitates. As Rome turned to the light of the gospel, however, that old Roman spirit with its old Roman language bequeathed to the rising Christian civilization a vocabulary of religion. Indeed, the word religio can scarcely be translated anymore because what it signified to the Latin mind—a whole nexus of ritual and feeling that binds a community together—will strike modern secular society as nothing but a silly costume party. This society knows how to be flippant over serious things, but where it sees its flippancy as characteristic of enlightenment, its Roman forebears would have seen it as characteristic of nothing but barbarism.

Waugh's Helena

I wanted to briefly share a favorite passage from near the end of Evelyn Waugh’s beautiful novel, Helena. The first time I listened to this passage, I can still recall where I was on the highway from Lexington to Louisville. It spoke so directly to me that I wept.

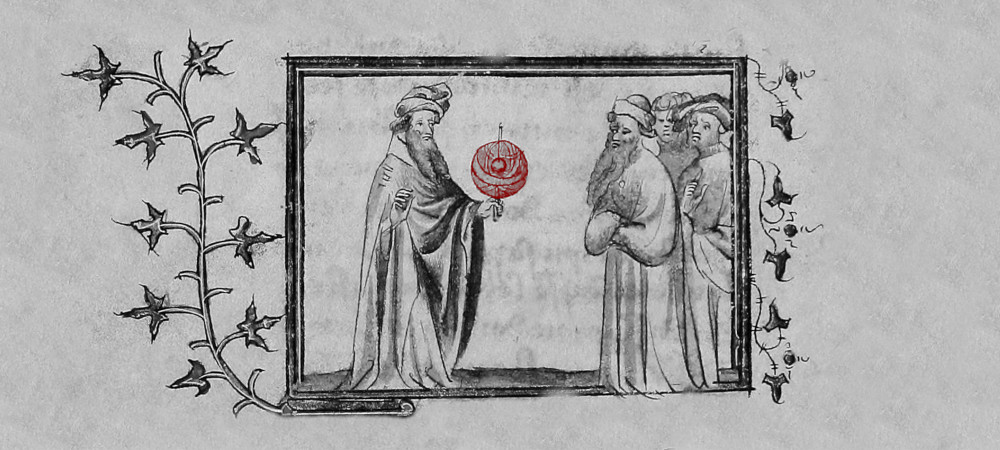

The novel follows St. Helena (sometimes known as St. Helen), the mother of Constantine. Much of the novel is a meditation on the conversion of the Roman Empire, especially the transition from Christianity being a marginal affair to something possible for the upper classes.

Toward the end of the novel, Helena makes a pilgrimage to Bethlehem, and here she makes a prayer to the three wise men, a moving expression of the paradox we find in St. Matthew’s gospel that “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God,” and yet, “…with God all things are possible.”1

“You are my especial patrons,” said Helena, “and patrons of all late-comers, of all who have had a tedious journey to make to the truth, of all who are confused with knowledge and speculation, of all who through politeness make themselves partners in guilt, of all who stand in danger by reason of their talents.”

“Dear cousins, pray for me,” said Helena, “and for my poor overloaded son. May he, too, before the end find kneeling-space in the straw. Pray for the great, lest they perish utterly. And pray for Lactantius and Marcias and the young poets of Trèves and for the souls of my wild, blind ancestors; for their sly foe Odysseus and for the great Longinus.”

“For His sake who did not reject your curious gifts, pray always for the learned, the oblique, the delicate. Let them not be quite forgotten at the Throne of God when the simple come into their kingdom.”

The Kingdom of Heaven belongs to the simple; it is their kingdom. And yet…the grace of God may extend even to the rich, the powerful, the sophistocated, even to an emperor like Constantine and a queen like his mother. What a happy inversion! What a hope! That humble barn of Bethlehem has room enough for the whole world, and the only hope of the great is, like Constantine, to find before the end “kneeling-space in the straw.”

There is also here a hope for classical culture, “the souls of my wild, blind ancestors; for their sly foe Odysseus and for the great Longinus.” This culture receives some redemption not on its own merits, but because it, like Constantine, finds some “kneeling-space” by the grace of God.

Matthew 10:25–27.↩︎

Logos as Intelligibility and Intelligence Video

Virtue and Martial Nobility

I have been thinking for a while now about the etymological connection between Arete (“virtue” or “excellence”) and Ares (the God of War).1 A similar connection exists in Latin between Virtus and Vir (“man” in the sense of “masculine”).

I think there is something in the history of the idea of virtue that relates to the idea of martial nobility that is almost entirely absent from high culture after the World Wars, or rather I should say that the connection has become almost entirely negative: “dulce et decorum est” and all that.

Here we see Arthegal, the ideal knight of Justice, from the court of Spencer’s Faerie Queene (1590), with his sword Chrysaor, painted by John Hamilton Mortimer (1778).

On Facebook, one of my scholarly friends called this etymology into question. My source is the entry for Ares in the Liddell and Scott Greek Lexicon. I confess that am unqualified to comment on the linguistics here and for all I know the etymological derivation may be different. My interest, however, is not really linguistics but philosophy. The entry in the lexicon simply got me thinking down these lines.↩︎

Logos as Intelligibility and Intelligence

In my last post, I focused on what we might call the “objective” side of λόγος, that is the meanings of the word that have to do with the arrangement of elements into structured wholes “out there” in real objects in the real world. In this post, I would like to focus on the “subjective” side of λόγος, that is the meanings of the word that have to do with rational consciousness. Philosophers frequently refer to the objective side of λόγος by talking about the “intelligibility” of structures or patters that we find in the world, there to be discovered. Conversely, we frequently refer to the subjective side of λόγος by talking about the “intelligence” of rational beings who go around doing the discovering. Understanding the distinction between intelligibility and intelligence and especially the causal interaction between the two will prove essential for understanding the Christian Platonic tradition.

Cosmos and Logos

When I was a child I used to tell people that I wanted to be a cosmologist, but they frequently took me to be saying “cosmetologist.” The link between such disparate fields as astrophysics and hairdressing only became clear when I took Greek as a college student and learned that the verb κοσμεῖν means “to arrange.” It applies to the person arranging hair and makeup and to the Demiurge arranging the stars in the heavens. In both cases specific parts are given order in relation to one another in such a way that they form a beautiful whole.

Different Meanings of Substance

The term “substance” functions as a key element in a number of important philosophical and theological arguments. At first glance, it appears to be a rather simple word that we use all the time, but this disguises several layers of complexity that often lead to confusion. “Substance” can have quite different senses in different philosophical contexts, sometimes directly at odds with each other. It will be helpful, then, to untangle a few of these different meanings so that we can keep our future discussions clear.

Right away, we can set to one side a couple meanings peculiar to the way that the word “substance” is used in English. Perhaps the most common is the use of “substance” to mean “stuff.” For example, we can imagine Star Trek characters finding a “strange substance” on the surface of a planet, which appears as a thick black goop. Philosophers will instead prefer the terms “matter” and “material” for this.

We can also set aside another sense of the English term that does not have a direct bearing on philosophy: in older English, “substance” can mean “wealth” or “livelihood.” One can read in Jane Austen, for example, someone described as a “man of substance,” meaning that he is rich.

Next, philosophers often use “substance” as a standard translation for Aristotle’s term οὐσία. This is not the place to give a full account of Aristotle’s philosophy of substance, but we can note briefly the way he uses the term in the Categories and the Metaphysics. In the Categories, Aristotle distinguishes between “primary” and “secondary” substance. Primary substance refers to a particular entity as the bearer of properties. Secondary substance refers to the species or genera to which these primary substances belong. For example, primary substance would refer to Socrates, while secondary substance would refer to Man or Animal. This simple distinction becomes much more complex in the Metaphysics, and there is scholarly dispute regarding how we are ultimately to interpret Aristotle’s view of substance in this work. We can gloss over these nuances for now, however, and say broadly that Aristotle comes to conceive of substance here as that which is most real.

Jordan Peterson and Platonic Realism

As Jordan Peterson rose to popularity a few years ago, I noticed a corresponding rise in people talking about symbolism, archetype, and meaning. Peterson frequently talks about these issues in a way that appeals deeply to thinking Christians and especially Christian Platonists like myself. In important ways, however, the approach Peterson takes, based on Carl Jung, differs dramatically from Platonic realism. While I may be competent to give a brief outline of what I mean by Platonic realism, I consider myself very much a student in the realm of Jungian archetypes. If anyone can set me straight, please do so. I’ll do my best, however, to articulate an important bridge that I see between the Jungian understanding and the Platonic, while cautioning against an important contrast.